By John Mauldin | 31 August 2008

|

I think we're at a watershed moment, what Peter Bernstein defines as an "epochal event," with the very order of the investment world changing as it did in 1929, in 1950, in 1981, where a number of things came together— it wasn't just one thing but a number of events happening that conspired to change the nature of what worked in the investment world for the next period of time [[aka, TEOTWAWKI: normxxx]]. It took most people a decade after 1981-2 to recognize that we were in a different period, because we make our future expectations out of past experience. It's very hard for us to recognize a watershed moment in the process. We're going to look back in five or ten years and go, "Wow, things changed." As we will see, it's going to be a change that's going to cost people in their portfolios and in their retirement habits.

We're going to look at a number of different concepts and separate ideas that in and of themselves don't make that much difference. But I think their confluence in the present moment is going to change things. Now, some of this is new, some of it is old. The old stuff we're going to fly through. Most of you have been reading me for a while now, and you've got the concepts down. So let's start.

The first thing to note is that we're in a Muddle Through Economy. We're in a recession that's fueled by the bursting of two bubbles: the housing bubble and the credit bubble/crisis. The real question is: when do we come out of the recession? At what time do we resume trend growth, which is 3 to 3.5 percent a year?

I believe that over the next 20 years the US economy will grow at roughly a rate of 3 percent compounded, in real terms. But I believe that we have some headwinds for the next year or two [[I would put it somewhat longer, until 2010 or 2011: normxxx]]. So I think the real bottom of this economic cycle will be later this year [[I would put it about the third quarter of 2009: normxxx]], during the fourth quarter and possibly into the first quarter of next year. But it will take two years, for reasons we are going to get into, to get back to long-term trend growth. It will take much longer than normal because the things that created the problem— the housing bubble and the credit crisis— aren't things that can respond to Fed policy, and they aren't things that can respond to the normal cycles. And, it's going to take a long time to work through these.

To begin with, we had an investor-driven transaction bubble in housing. There were 48% more houses built since 2005 than should have been built, if you were simply looking at trends.

What that means is there are 3.5 million homes we have to work through. Now, that means that the 8 or 9 hundred thousand homes that we're now down to building a year, is going to end up going down to 400,000. It's going to take some time to work through those excess homes— for the prices to drop enough that people can go in and buy them or rent them. We are probably talking 2011 before we finally work through this housing crisis and get back to a normal market where housing contributes significantly to GDP growth.

Sales activity is probably going to correct another 30 percent. That's not fun. By the middle to the end of this year, sales are going to be really low. As a side issue, those of you who like to invest in real estate and actually want to own a home to rent are going to have some good opportunities.

Let's look at the credit crisis very quickly. We vaporized 60 percent to the shadow banking system, the SIVs and CDOs, the people who actually bought US mortgages, who bought student loans, who bought credit cards, who bought car loans. That's gone and it's never coming back. As we'll see, it's going to take well into the next decade for us to create a completely new infrastructure to replace the broken one.

It took decades to get to where we were last year. I don't think it will take decades to fully recover, but it's going to take five, six, seven years to get to a reasonable semblence of a decent recovery. That means things are going to be difficult if you want to borrow money. [[All of those 'easy money credit' sources have gone bone dry.: normxxx]] Credit spreads are going to be wider; it's going to affect you more. By the way, if you're in business, if you're paying more, it's going to put pressure on your profits.

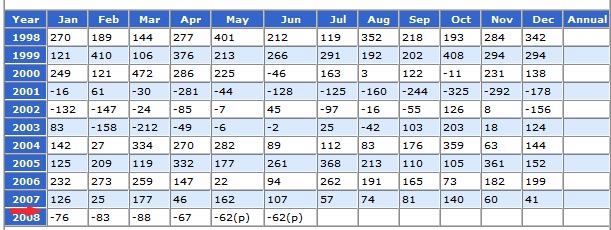

Let's look at GDP growth for the last ten years, with and without mortgage equity withdrawal.

Without MEW, we would have had two years, in 2001 and 2002, with negative GDP growth. We're not going to go get those levels of mortgage equity withdrawals today, not in this environment. We're still seeing some cash-out borrowing, but it's getting more and more difficult; and as home values drop, there are going to be fewer and fewer people pulling less and less money out of the "home ATMs." As Paul McCulley says, your home ATM is starting to spit out negative twenty-dollar bills.

That means consumer spending is going to continue to slow. We haven't had a consumer recession since 1990-91. There are a lot of people today who have kind of forgotten that consumer spending can actually slow down. That's going to happen from lower mortgage equity withdrawals, and it's going to happen because of higher gas and energy costs that are displacing normal spending. You've got to fill up your Ford F-150 to be able to get to work.

I saw $4 a gallon gasoline when we arrived in La Jolla. I mean, I guess around here people don't really pay attention, but that means it would cost a hundred bucks to fill up my big SUV. That's just a lot of money. That's a hundred bucks I can't spend on something else— on clothes or kids or education. It means I'm going to be consuming less.

We're in a recession. Recessions by definition mean that we're going to be seeing rising unemployment. We're already up past 5.5 percent. We'll probably see 6 percent and maybe higher. We're not going to see the 9 and 10 percents like we did in the '70s or '80s, because we're not as subject to the manufacturing cycle as we were back then [[but mainly because they have made major changes in the way unemployment statistics are calculated since then: normxxx]]. That's both good and bad. We don't have that boom-bust in the manufacturing world.

We're seeing a bust in the construction world and we're starting to see commercial lending and commercial building go down. But I don't think we're going to see the large 8 and 9 percent unemployment rates that we typically see in a recession. But still, if you see rising unemployment— and unemployment rises by 20 percent, from 5 to 6%— that means those people are going to have less money and they're not going to be spending it.

We're seeing inflation in an environment of low real-income growth. Inflation is running over 4 percent now. And real-income growth is running a little bit less. While we may see some nominal growth in consumer spending, real spending is going to be dropping over the next year. That has some consequences that we'll talk about later. Also, consumer spending is going to drop because we have less availability of easy credit. Now, it probably hasn't as yet hit the readers of this post much, if at all.

But there is a wave of letters going out from credit card companies, cutting people's credit lines, cutting people's home mortgage lines. There are a lot of people actually hitting their home equity credit lines and putting it in a savings account because they're afraid that it's going away. They're afraid that they may not be able to get the cash when they need it. "What happens if I lose my job? I better get the cash, and I'll pay the difference in interest costs just to make sure that I'm OK." That's happening a lot.

In summary, lower mortgage equity withdrawals, higher gas and energy costs, rising unemployment, inflation in an environment of low real-income growth, and less availability of cheap and easy credit are all contributing factors to slowing consumer spending.

This has three major effects. First, lower corporate earnings. We're in a period where earnings disappointments are going to be the rule and not the exception. We're going to go into this in detail in just a little bit. But GE wasn't a one-off announcement. Yes, it was their financial system. But we're going to see a lot of earnings disappointments from all sorts of retailers, from all sorts of companies, for a variety of reasons. We're going to go over the documentation to illustrate that.

Second, lower corporate profits put pressure on the stock market. There's a relationship between earnings, valuations, and stock prices. And third, that also means we're going to see lower than expected long-term returns. That's going to be a problem for people who are looking for traditional assets to be the bulk of the growth for their retirement portfolios.

Now, I think we're still in a bear market. Remember that in 2000 and 2001, we had three corrections of over plus 20% percent and one in the plus 30% range. It's not unusual to see large corrections inside an overall bear market. Why do I think we're in a bear market? Long-term markets— and we're going to talk long term for a bit and then talk about the shorter term— long-term markets in bear cycles have several characteristics.

Number one, they all start with high P/E ratios. Now, Vitaliy Katsenelson, who wrote my e-letter this week so that I could be here, lays out what he calls "cowardly lion markets," as distinct from bear markets, because stocks tend to go sideways for a long period of time. We'll talk about why that is in a minute, but I think he's right on that.

You are told that you should invest for the long run. Twenty years for a lot of people is the long run. However, what they do not tell you is that you can see negative real stock market returns over 20 years [[notice the clustering between -3% and 0%: normxxx]]. It's happened four or five times. So when you're reading in somebody's book that says, "Hey stocks are going to compound at 11 percent a year" or whatever la-la number can be seduced from the data, think twice.

You are told that you should invest for the long run. Twenty years for a lot of people is the long run. However, what they do not tell you is that you can see negative real stock market returns over 20 years [[notice the clustering between -3% and 0%: normxxx]]. It's happened four or five times. So when you're reading in somebody's book that says, "Hey stocks are going to compound at 11 percent a year" or whatever la-la number can be seduced from the data, think twice.In secular bear markets, you can have returns for long periods of time from zero to 3 percent [[notice the clustering between 0% and 3% in the chart at left, above: normxxx]], every 15 to 30 years. We're kind of starting one here again. If you went to Standard and Poor's website in March of 2007 and you asked what the earnings were going to be for 2008, their analysts said that earnings would be $92 for 2008. Two months later, at the end of the year in December 2007— this is eight months ago— they were projecting $84. In February, it was $71.20. Today Merrill Lynch estimates that earnings could drop to as low as $45 next year. Notice a trend here?

When you go into a recession, analysts begin to project lower earnings. They keep ratcheting them down. What do they use to project future earnings? Past performance. There are very few analysts who actually go out and say, "OK, how is this company going to perform in a recession?" They all say, "The company that I cover is an exception." This is how they're going to cover it, because they're talking to management.

And when's the last time management said, "Oh man, we're really going to get clobbered; there's a recession coming." Not if they want to keep their jobs. John Chambers will be telling us that Cisco's going to be doing wonderfully, just like he did all of 1999, all of 2000 and all of 2001.

Now, what does this mean for P/E ratios? Several months ago, it was estimated, based on prices, that the P/E ratio for the end of the last quarter would be 20.5. More recently, as companies marked their earnings down, the P/E ratio rose to 22.5. For the end of September, third quarter, they were projecting the P/E ratio would be 21. Today they're projecting that if the market stayed at the same price, it would be 28. Now, does anyone think we're going to see a P/E ratio of 28 at the end of the third quarter? People are going to be projecting positive earnings forward— and we're going to see one earnings 'surprise' after another.

Remember, it takes three to four really good earnings disappointments to reach a point where investors really begin to understand that things are different, because we project future performance from past performance. When past performance disappoints us three or four times, then we begin to project negative performance, and that's when the stock market drops. It's not that the stock market is telling us that things are going to be better. It's that we have expectations of things getting better because that's what our past experience has been— so we need those disappointments.

This is from Vitaliy Katsenelson's book: If you take 10-year trailing P/Es— you average them together so you don't have the effect of just one year— you find that valuations go from high to low from where bull markets start, in what he calls a 'range-bound' market or what I would call a 'secular bear'.

They go from high valuations to low valuations and back. Around 2000 we were at 48. It's down to 30 today on those long, ten-year runs, and it always corrects below the mean. Valuations are mean-reverting machines.

If you just look at one year, you get the same effect. You have a P/E average of 15— remember they're projecting 28. You don't have a projection of 28 in a recession and not have the stock market feel that. The current situation is even worse than the chart depicts, because on the most recent as-reported 12-month P/E ratio for the S&P 500 was 22.87 through the end of the second quarter.

We have a LONG ways to go to revert to the mean. The only way for that to happen is for earnings to rise or for stock prices to fall, or some combination of both. Otherwise, you have to suggest we are in an era of permanently and significantly higher stock valuations. (Remember, these cycles last an average of 17 years; we are only about 8 years into this one.)

Unrealistic Expectations

Valuations are important. They are the key to long-term returns. Your expected returns in any one 10-year period highly correlates with where you start investing. If you start when stocks are cheapest, you're going to compound at about 11 percent. But if you start when they're the most expensive, at an average PE of 22, you're going to compound at about 3.2 percent over the next 10 years.

For the people and the pension funds that are expecting to get the 8 or 9 percent that they've got written into their returns in their equity portfolios, that's not good news. The following chart from my friends at Plexus illustrates the point. I should note that this calculation works not just on US stocks but in every market that I have seen studied. This is a fundamental principle of investing. So, what we have is a situation where many aging Baby Boomers and the pension funds and insurance companies which are investing on their behalf are not likely to be able to get the returns they need in order to meet their obligations from traditional US equity holdings.

The Boomers Break The Deal

Now, let's jump to another subject. Boomers (and that would be me and most of the people reading this) are going to break the deal our fathers and grandfathers made with our kids: that we would die in an actuarially and statistically definable timeframe. Without being able to know how large populations will "shuffle off this mortal coil," things like planning for Social Security and Medicare, insurance, and pension plans become a very dicey business. And the news we Boomers have for our kids and the actuaries who actually care about these things? We're not going to die on time.

We're going to live longer, and this is going to have consequences for everyone's investment portfolios. We're not going to get into why we're going to live longer; the simple answer is that medicine is advancing. The boomers are going to live, on average, about 10 years longer than they statistically should; my kids and those under 40 are going to live, on average, a lot longer. But that is a topic for another speech. Simple fact: the majority of Boomers don't have enough savings. Numerous studies show they haven't saved enough to be able to retire. They certainly haven't saved enough if they're going to want to live longer and take advantage of medicine to do that.

If we start living longer, there are going to be massive problems with pensions and annuities, because there are actuarial tables that say people are going to die along this timeline. If all of a sudden— and over a ten— or fifteen-year period would be all of a sudden from an actuarial or pension fund point of view— people start living longer, it's going to mean that those who pay will run out of money sooner rather than later. Since they will notice the problem long before they get to the end of the money, they will have some time to make adjustments. That means they are either going to have to lower pension payments, or they're going to have to get more money from somewhere (either increased contributions or increased returns).

Now, if they're in a period where they're projecting 8-percent returns from their equity funds, and they're not getting 8 percent— if they're only getting a long-term 4 to 6 percent from here over the next ten or fifteen years— that's a big problem in funding. Public pension funds have the same problem, but it is much worse. They're a couple of trillion dollars underfunded. This is why you're seeing California cities beginning to declare bankruptcy, because they're having to tell their firemen and policemen, "We can't pay you what we agreed to pay you; let's renegotiate something more realistic."

It's going to get ugly in a lot of cities. In San Diego, it's already a huge problem. Politicians promised the police and fire and the city people all sorts of wonderful things, they got their votes, and those that did the promising are not going to have to be there to deal with the problem when it becomes a crisis in a few years. Isn't politics wonderful? Promise anything for votes today and let our kids pay for it tomorrow.

The problems that we're projecting for Social Security and the underfunding today are massively understated. We're going to have to pay a lot more for Social Security than we expected, because we're going to live longer. And the younger generation isn't going to be real happy about having to pay a lot more money to older people who are living longer and don't want to (or can't) go back to work. When they started Social Security, retirement was at 65 and the average person died at 66. There wasn't a lot of expected payout. Now people who make it to 65 will on average live well into their 80s and are soon going to live well into their 90s.

This is going to create generational issues. It will also demand an increase in taxes. It's coming guys, and you are the target. You've got a big target right on your wallet. As in California: "If you're making over a million, we want to take an extra one percent"— that's going to happen in so many states.

A Nation Of Wal-Mart Greeters

Now, let's look at it from another angle. Let's say you're getting ready to retire, you're 65, and you put your money into the most aggressive portfolio you can that historically has given the best returns— that's the stock market— and you're going to take 5 percent out a year. That seems a reasonable number. A lot of people say, "We can take 5 percent of our money out every year."

What would happen? Well, remember that graph I just showed you? Depending on the P/E ratio when you retired, if you started out when stocks were the 25 percent most expensive, over 50 percent of the time you'd run out of money in an average of about 21 years. Look at the table below from my good friend Ed Easterling of Crestmont Research.

Even if you started when stocks were the 25 percent least expensive, you would run out of money before the end of your remaining 30 years about 1 out of 20 times. If I came to you and said, "You know, you've got a medical problem and we're going to have to have an operation tomorrow. And oh, by the way, you've got a 5 percent chance of dying," you would probably be quite nervous.

What I'm telling you now is, if you get too aggressive with your retirement and investment assumptions in a Muddle Through World, especially at the beginning, you're going to end up with problems. We could end up with a nation of Wal-Mart greeters. (Not that there is anything wrong with those happy people who greet me! It is just not the retirement most people plan for.)

But many in the Boomer generation that is getting ready to retire have not made adequate plans and are assuming very optimistic future returns. So are their pension plans. You're going to be living with neighbors and friends who have this problem. And not just neighbors and friends but voters looking for someone to solve their financial problems with your tax dollars.

The Wealth Of Nations

Now, let's look at the next topic: the wealth of nations. From 1981 to 2006, our national wealth in terms of the houses we own, stocks we own, real estate, bonds, businesses— everything— our national wealth (or maybe it's better to say, the prices we put on our assets) grew from $10 trillion to $57 trillion. Over very long periods of time national wealth is by definition a mean-reversion machine. Over 40 or 50 years national wealth has to revert to the growth in nominal GDP. That's just the way the economics and the math work out.

Basically, the principle is that trees cannot grow to the sky. Just as total corporate profits cannot grow faster than the overall economy over long periods of time, neither can national wealth. Think of Japan. At one point in 1989, relatively small areas of Tokyo were worth more than the total real estate of California. And then the bubble burst and Japanese national wealth decreased and grew much less than GDP and is now in line with the long-term nominal growth of GDP.

In the US, long-term growth of nominal GDP is about 5.5 percent. We've actually grown by 7.2 percent for the last 25 years. To revert to the mean means that over the next 15 years, maybe more if we're lucky, we're going to see nominal wealth grow between 2.5 and 3 percent. That's a major headwind and a major dislocation from the experience that we've had. Investors have been expecting to get the past 25 years to repeat themselves. The laws of economics suggest that cannot be the case.

We have seen a monster growth in equities in terms of total market cap, even given the flat growth of the last ten years. We all know about the housing market. Remember the part above where we talked about stock market valuations being mean reverting? We are watching housing values come down. What we are going to see is a very difficult period for asset growth in precisely the two areas where investors tend to concentrate their portfolios: US stocks and housing. Using history as our guide, that period could last for another 5-7 years.

Let me hasten to add that I am not suggesting that the stock market will not go up over the next seven years. What I am suggesting is that we could be in a period like 1974 through 1982 where the stock market did indeed go up over those eight years (in fits and starts), but profits [[and inflation: normxxx]] went up even faster. Thus, P/E ratios were in single digits by 1982.

Let's begin to put all this together. What are the requirements of retirement, whether for individuals or pension funds? I think I made the case that traditional investments are going to underperform— that's the stock markets of all the developed countries and to some degree the emerging markets. But, you've got to have income and savings if you want to retire.

You can't throw caution to the winds and invest in the most risky and volatile assets in hopes of getting the returns you need. Hope is not a strategy. You do not want to take much risk with retirement assets, which will be hard to replace. You've got to figure out, "How do I get income in an era of low interest and low CD rates?" And, "How do I convert my savings, and what do I put them in that will give me that income?"

If you're a pension fund, if you're expecting 8 percent from your equity portfolios and you're only getting 2 to 3, at some point you're going to get nervous. You're going to realize you've got to do something else. Same thing with insurance companies and annuities. That means there's going to be a drive for more absolute-return-type funds. The problem is, the place to go for reliable absolute returns is smaller funds.

But most large pension funds are trying to put one or five or ten billion to work, not a few million. And if everybody tries to get in the water at the same time, the pond could get very crowded. Now, full circle. This is where I think the credit crisis is going to come to the rescue. I think we're having a reverse-Minsky moment. Hyman Minksy said that stability breeds instability. The longer something is stable, the more instability there is when that moment of instability happens. The crisis period of instability is called a Minsky moment.

So we had a long period of time of remarkable stability in the credit markets, then there were a few cracks here and there, and now we're having the crisis which started in July of 2007. The losses in both housing values and bonds will be in the trillions of dollars. Why? Because stability creates an environment for people to feel safer taking on more risk and leverage. It's just part of human nature. Note: This is not just an American disease. It has happened since the Medes were trading with the Persians and in every corner of the earth.

But now I think we will get kind of a reverse of this pattern, a reverse-Minsky moment, where instability will breed stability, because we as investors, we as human beings, don't like instability; and we'll do whatever it takes and whatever we need to do to demand a return to a stable investment environment. So, two forces that I have touched on in this speech are going to come together. First, we have destroyed— we've vaporized— 60 percent of the buyers for the structured credit market and badly wounded the survivors. We've got to create something to substitute for that, as we need a smoothly functioning debt market to allow for growth and a healthy business environment.

It is absolutely necessary for individuals to have access to credit for purchases. If we all had to go to cash, it would be a disaster of biblical proportions. Second, there is a need for equity-like returns on the part of investors of all sizes, from the smallest to the largest pension funds. If you can't get 8-10% from equities over the next ten years, where do you turn? I think what we're going to end up creating, and what we're already beginning to see happen, is going to grow into a huge wave: we're going to see the creation of a series of absolute-return funds that I think of as private credit funds. I don't really want to call them hedge funds, because they're not really hedging anything.

For all intents and purposes they're going to look like banks. They're going to put their green eyeshades on, and when they loan you money, they're actually going to expect it to come back. And they're going to expect it to come back with a level of risk return commensurate with the level of risk they're taking. Instead of going through the messy business of getting depositors to put money into accounts, depositors who can come in and out, and having to service them and let them write checks and all of that stuff, they're going to go to investors and say, "Give me $100 million or $200 million or $500 million, and I can attack this market and give out loans in this manner, and I can generate these returns— 8 percent, 9 percent, 12 percent."

Maybe some of these markets we can lever up two or three times. Two or three times leverage sometimes sounds like a lot. But our average commercial bank is leveraged 10 times. Our investment banks are leveraged 25 times or more. Two to three times in a properly structured debt portfolio isn't a lot of leverage, but it can give you high single-digit or low double-digit, relatively stable returns. These private credit funds will look like private equity, in that they will have long lock-up periods, so that the duration of the investment somewhat matches the duration of the loans made.

It is the mismatch of duration that has created much of the problem in the current market. All sorts of investment vehicles like SIVs, CDOs, etc. borrowed short-term money and made long-term investments. So, we've got demand from two sources. We've got a demand from a retiring generation, from a pension generation, demanding equity-like return, when they can't get equity-like returns from the equity market. We've got a demand for credit funds— we've got to replace the people we've vaporized.

We're going to see the creation, I think, of a multi-trillion-dollar marketplace of people, pensions, and investors looking to be able to attack those credit markets. Initially it will be for large funds and investors, but it will eventually filter down to structures that the average person can get into. For a lot of us, we're going to see the ability to find stable returns, equity-like returns, show up at our door. And one way to attack this initially may be funds-of-funds, where you can spread your risk over a number of these types of funds and managers.

It's going to require somebody to go in and actually analyze the banker who's making the loans to see if he's, you know, a real banker. Because we know we don't want those guys from Wall Street who made the last set of loans running our funds, at least not until they've gone back to school to learn what a loan is. I know I am leaving a lot to be said, but this piece is already too long. Let me say in closing that while a broad asset class that I call private credit funds will share some characteristics, the individual funds themselves will be quite different as to what type of credit they provide (housing, commercial real estate, auto, corporate, credit card, student, and a score of other areas), what types of returns they target, who their customers are, and who their investors are.

Further, while private credit will initially compete with banks, I think that at some point banks will see this as an opportunity to return to their recent and very profitable model, which is to originate loans and then sell them off. Properly run, private credit will be good for the managers as well as the investors. And there is no reason that the management cannot be the banks. In some ways, they have an obvious advantage in this market, as it will be easier for them to attract large investors like pension funds and sovereign wealth funds.

This is a new era. We're going to have to shift from thinking that broad-based stock funds are for the long run. Over the last ten years, if you invested in the S&P 500, your net asset value is flat and dividends have badly underperformed inflation. With today's high inflation and lower earnings, that underperformance could last another lengthy period. If your time horizon is 30 years, then maybe you can talk about the long run. But if your time horizon is 5-10 years before retirement, you need to think about your definition of long run.

Now, you can buy individual stocks if you're a great stock picker or find a manager who is rather good at picking stocks. Donald Coxe was talking to us about agriculture, which I agree is in a bull market. There are other types of technologies— I think the biotech world is going to be huge, starting in the next decade. There are going to be places where we can go into specific target areas and make equity-like returns from equities. But I don't think we are going to be able to do it in a cavalier, "I'm going to put my 401(k) into the Vanguard 500" manner and walk away. It's going to be a challenge for your retirement portfolio if you do.

Retirement in today's world is going to take considerably more thought (and funds!) than was traditionally believed. I encourage you to look at your own situation and carefully analyze the assumptions you have made.

|

.

Stock Market Valuation And Reversion To The Mean

Market Cycle Math: Where Are We Today? Analyze and Strategize

|

Active Value Investing: Making Money in Range-Bound Markets (Wiley Finance)

Active Value Investing: Making Money in Range-Bound Markets (Wiley Finance)In his recent book, "Active Value Investing: Making Money in Range-Bound Markets" (Wiley, 2007), Vitaliy Katsenelson exhorted investors to fasten their seat belts and lower expectations for the next decade or so. He also provides a strategy for improving returns in this environment, what he calls 'range-bound' or 'cowardly lion' markets. Long-time readers will recognize some themes consistent with my own research, but Vitaliy adds some very interesting twists that I believe will make you think. In today's letter, Vitaliy runs through his analysis of what will happen and provides an overview of how investors can make money in what will otherwise be an ocean of stagnant returns. Let me also highly recommend Vitaliy's book— I think as you read today's letter, you will get a sense of why I am so enthusiastic about his work. ~~John Mauldin

Bull, Bear, And 'Cowardly Lion' Markets

By Vitaliy Katsenelson | 11 April 2008

For the next dozen years or so the US broad stock markets will be a wild roller-coaster ride. The Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 index will go up and down (and in the process will set all-time highs and multiyear lows), stagnate, and trade in a tight range. At some point during the ride, index investors AND buy and hold stock collectors will realize that their portfolios aren't showing much of a return. I know this prediction has a mild sci-fi feel to it. After all, how could I possibly know what the market will do, especially that far into the future?

Though I'll explain in more detail in just a second why I have the audacity to make this prediction, let me offer you a little factoid: over the last 200 years, every full-blown, long-lasting (secular) bull market (and we just had a supersized one from 1982 to 2000) was followed by a range-bound market that lasted about 15 years. Yes, this happened every time, with the exception of the Great Depression, over the last two centuries.

Though we tend to think about market cycles in binary terms— bull (rising) or bear (declining)— in the long run markets spend a lot more time in 'bull' or in 'range-bound' (sideways) states, roughly half in each, and visit a bear cage a lot less often then we think. This distinction between bear and range-bound markets is extremely important, as you'd invest very differently in one versus the other. Are bull markets driven by superfast economic growth? Are range-bound markets caused by subpar economic growth? Could the subpar market performance be related to high or low inflation?

The answer to all these questions is undoubtedly— "no." Though it is hard to observe in the everyday noise of the stock market, in the long run stock prices are driven by two factors: earnings growth (or decline) and/or price-to-earnings expansion (or contraction). As is apparent from Exhibits 1 & 2, either by a decade at a time or a market cycle at a time, it is difficult to find a link between stock performance and the economy (e.g., GDP, corporate earnings growth, or inflation). The connection does exist, but periods of disconnect appear to last for decades at a time.

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 2

What about interest rates? Exhibit 3 shows P/Es for the S&P 500 (based on one-year trailing earnings) and inverse long-term bond yields— the implied P/E— the famous Fed Model. This model, despite its name, is NOT endorsed by the Fed; it indicates the existence of a tight relationship between (inverse of) long-term Treasury bonds and P/Es of the S&P 500.

Exhibit 3

By taking a look at the last full 1966-2000 range-bound/bull market cycle (see Exhibit 3), we can see that the Fed Model perfectly predicted the direction of equities in relation to interest rates (okay, assuming you could predict interest rates). Long-term interest rates were rising from 1966 to 1982, while implied and actual P/Es were falling. Whereas from 1982 to 2000 interest rates were dropping, and implied and actual P/Es were rising. Intellectually that makes sense, because stocks and bonds compete for investors' capital, and thus higher interest rates make equities less attractive and vice versa.

|

However, it is hard to find ANY relationship between interest rates and the animal with its name on the secular market if you look at the first 66 years of the 20th century. None! It is difficult to dismiss the role interest rates play in stock valuations, but they seem to play a decided second fiddle (or lesser) in the orchestra conducted by economic growth and valuation. If the Fed Model worked flawlessly, how could we explain declining P/Es of Japanese stocks in the last decade of the 20th century, when interest rates declined and were scratching zero levels?

It is valuation! If earnings growth in the long run remains consistent with the past, P/E is the wild card that is responsible for future returns. Though continued economic growth appears to be a wildly optimistic assumption given the meltdown of the housing industry in particular, and job layoffs, it is not particularly unrealistic to predict that we will see economic growth overall. With the exception of the Great Depression (see Exhibits 1 & 2), though it had its ups and downs, economic growth was fairly stable throughout the 20th century. Earnings, though more volatile than real GDP, also grew consistently decade after decade, paying little or no attention to the animal lending its name to the stock market.

Bull, bear ... or cowardly lion— my pet name for range-bound markets, whose bursts of occasional bravery lead to stock appreciation, but which are ultimately overtaken by equivalent bouts of fear that leads to a subsequent rapid descent. Though economic fluctuations were responsible for short-term (cyclical) market volatility, as long as economic performance was not far from the average, long-term market cycles were either bull or range-bound. Valuation— the change in price to earnings, its expansion or contraction— was the wild card that was mainly responsible for markets being in a bull or range-bound state.

Market Cycle Math

So let's examine the stock market math for secular bull, range-bound, and bear markets. The following Exhibit 4 shows sources of price appreciation in past bull, range-bound, and bear markets. During bull markets, a vibrant, peaceful combination of P/E expansion (a staple of bull markets, a great source of return) and earnings growth brings outsize returns to jubilant investors. Prolonged bull markets start with below- and end with above-average P/Es.

Exhibit 4

P/Es are some of the most mean-reverting creatures, and range-bound markets act as clean-up guys: they rid us of the mess (i.e., they deflate those high P/Es) caused by bull markets, taking them down towards and actually below the mean. P/E compression wipes out most if not all earnings growth, resulting in zero (or nearly) price appreciation plus dividends.

Bear markets are range-bound markets' cousins; they share half of their DNA: high starting valuations. However, where in cowardly lion markets economic growth helps to soften the blow caused by P/E compression, during secular bear markets the economy is not there to help. Economic blues (runaway inflation, severe deflation, subpar or negative economic or earnings growth) add oil to the fire (started by high valuations) and bring devastating returns to investors.

A true secular bear market has not really taken place in the US, but one has occurred across the pond in Japan. The market decline caused by the Great Depression, though referred to as the greatest decline in US stocks in the 20th century, only lasted three years and thus doesn't really fit the traditional "secular" requirement of lasting more than five years. Japan's Nikkei 225 suffered (see Exhibit 5) through a true secular bear market: stock prices declined over 80 percent from their 1989-1991 highs until they bottomed in 2003 (the market seems to be coming back now). For more than a decade the country struggled with deflation caused by its banking system coming to a near halt on the heels of a collapsing real estate market and the bad loans that came with it. Of course, all this took place on the heels of a huge bull market, and thus very high valuations.

Exhibit 5

A unique aspect that contributed to the severity and longevity of the Japanese deflation was a cultural issue: the Japanese government intervened and did not allow structurally defunct companies to go bankrupt, thus tampering with the nucleus of capitalism (and Darwinism as well), creative destruction. I must admit, it seems that lately we've been importing a lot more from Japan than their cars and flat-screen TVs, as the US government steps in to "fix" our troubled financial firms. (In the following articles I argue against government bailing out homeowners and against the Fed bailing out the economy ).

Where Are We Today?

Today stocks may appear cheap at first glance, at least if you look at valuations of the late 1990s. They are not! To minimize the impact of cyclical profit volatility, let's first take a look at stock market historical and current valuations, based on 10-year trailing earnings, as shown in Exhibit 6. This way we capture a full economic cycle.

Exhibit 6

The conclusions we can draw are:

- Secular bull markets end at P/Es much above average. The 1982-2000 bull market ended at the highest valuations ever!

- Secular range-bound markets ended when P/Es were below average.

- Markets spent very little time at what is known to be a

Now, if you look at historical valuations where P/Es are computed based on one-year trailing earnings (see Exhibit 7), the picture is not that exciting but less grim. At about 18 times trailing earnings, US stocks don't appear that expensive. Unfortunately, the 'reasonable valuation for stocks' argument falls on its face once you realize that (pretax) profit margins are hovering at an all-time high of 11.5%, about 35% above their historical (since 1980) average of 8.5%. Similarly to P/Es, profit margins are extremely mean-reverting.

Exhibit 7

As companies start to earn above-average economic profits, new competition waltzes in and competes these excess profits away— arrivederci fat profit margins. Once this happens, the "E" in the "P/E" equation will decline as well, and P/Es will rise from 18 to 22. An additional point: as you see in Exhibit 8, margins don't have to revert and stop at the mean; historically they've usually gone below the mean— that is how the mean is created. (In the February 4th , 2008 issue of Barron's I rebuffed common arguments against profit-margin mean reversion.)

Exhibit 8

As a side note: The bulk of excesses in overall profit margins, 54.5% to be exact (see Exhibit 9), were in "stuff" stocks (i.e., energy, materials, and industrials). Profit margins will deflate when the global economy slows down. This goes far beyond oil and commodities. Companies that make "stuff," which historically have been very cyclical (today is no different), have benefitted from tremendous operational leverage that contributed to considerable improvement in margins. However, leverage works both ways: lower sales and high fixed costs will push margins to the other extreme.

Exhibit 9

Financials were responsible for 22% of the excess in margins, as they benefitted from tremendous liquidity hosed down by the Fed over recent years; now they are drowning in it. Their margins are compressing at a faster rate than you can read this.

Finally, the "new" economy stocks are responsible for 17% of the excess. However, I'd argue that these industries have transformed substantially since 1988, so that higher-margin software and services now account for a much larger portion of technology and telecom sales. It is kind of like Microsoft (ironically then the "new" economy) vs. IBM in 1988: the hardware company (the old economy) vs. the new. Of course IBM of today is lot more of a software and service company than the hardware company it was in the 1980s. Thus the "new" economy stocks should have higher margins than they did in 1988, but by how much? I don't know, but they likely will face a lower margin compression than "stuff" and financials.

The bottom line: Remember those long-term double-digit returns you were promised by stock market gurus during the last bull market? Well, an average passive, buy-and-hold, investor will be lucky to have very low single-digit returns for the long term. In fact, during the last 1966-1982 range-bound market, investors received almost zero real total returns.

Analyze And Strategize

Fairly depressing stuff, and it sounds like the investor is going to have to eat lower returns. However, there are strategies to improve portfolio performance so that one can do well, even in a trading range. Whether you are a buy-and-hold or stalwart value investor, there are opportunities that don't require you to 'day trade' (or even to 'swing trade') stocks. You don't have to change your investment philosophy, aka, 'strategy', but you have to tweak your stock analysis and 'tactics' a little to adapt it to range-bound markets.

Modify your analysis: To clarify, I created an analytical framework where stock analysis is broken down into three dimensions: Quality, Valuation, and Growth.

Quality. Though often it is in the eye of the beholder, in my book I clarify what constitutes a quality company (i.e., sustainable competitive advantage, strong balance sheet, great management, high return on capital, and a lot more). But the lesson here is, you want to compromise as little as possible on this dimension, because it is very difficult to recover from significant losses in the range-bound market. Stick to quality.

Growth. This dimension consists of earnings (cash flows), growth, and dividends. When you own companies that grow earnings, time is on your side. Dividends are extremely important in range-bound markets, in fact 90% of the returns in past range-bound markets came from dividends, vs. less than 20% in past bull markets. Also, today an average stock (i.e., S&P 500 index) yields only 1.7%. Do you really want 1.7% to be 90% of your total return?

Valuation. This dimension requires the most modification: the valuations that we saw in the 1982-2000 bull market are not coming back anytime soon, but don't step into what I call the relative valuation trap. Don't buy stocks based solely on their relative cheapness to their prices in the past, but rather based on what their future cash flows will bring. To combat a constant P/E compression, in the range-bound market increase your required margin of safety.

That value (i.e., low P/E stocks) beats growth (high-valuation stocks that have high expectations built in) has been historically documented by numerous studies. After doing extensive study of the 1966-1982 range-bound market, I found that value kills growth. Cheaper stocks had a lower P/E compression and generated bull-market-like returns, plus they had a natural advantage: their lower P/Es led to higher dividend yields. Stock selection matters in the range-bound market. Blindly throwing money at market indices— a strategy that did wonders in the past bull market— will bring market-like returns, which likely will not pay for your dream house or fund your retirement.

Strategize: Once you have determined, based on the Quality, Valuation, and Growth framework, what stocks are to be bought and at what prices, you can start applying a range-bound market strategy. A long-lasting secular range-bound market consists of many mini (months to several years long) cycles. For instance, the last 1966-1982 range-bound market consisted of five mini bull, five bear, and one range-bound market (See Exhibit 10).

Exhibit 10

Successful investing is a lonely place, as it requires an independent thought process that often goes contrary to the herd mentality. In the range-bound market, a contrarian mindset comes in especially handy, as you'll be selling when everyone else is buying. Your stocks will be hitting their fair value, and you'll be buying when everyone else is selling— during the mini bear markets.

This is not to suggest that you need to be a market timer, not at all. Market timing only looks easy with the benefit of hindsight, and it is very difficult to do on a consistent basis. Instead, time (price) individual stocks, one at a time. Buy when they are undervalued and sell when they are fairly valued, and repeat the process over and over again. In other words, instead of focusing on the bowling alley (the market) focus on the ball (individual stocks).

Selling is looked upon as a four-letter word, and therefore a sin, in a bull market. A buy-and-hold strategy (which is often just buy and forget to sell) is rewarded richly in secular bull markets— every time you made a "don't sell" decision, stocks go higher. And though buy and hold is not dead (for now) but merely in a coma (waiting for the next secular bull market), it takes investors to a place of no returns. Forgive yourself the "sin" of selling and become a buy-and-sell investor.

The almighty US constitutes 4% of the world population, but its stock market capitalization represents more than a third of the world's wealth. It has been comfortable for us to buy US stocks; it felt safe. However, by solely focusing on US stocks we are insulating ourselves from a greater pool of stocks to choose from. You don't need to become an Indiana Jones of international investing by venturing into fourth-world countries like South Paragama or Liberania (ok, I made those up, didn't want to offend folks in Turkmenistan or some other places heading towards the stone age), but there are plenty of countries that have a stable political regime and the rule of law.

I Could Be Wrong But I Doubt It

What if I am wrong and the range-bound market I describe is not in the cards? After all, history is prolific about the past but mute about the future. What if they find life on Venus and our economy starts growing at double digits and the secular bull market thunders upon us? Or the current credit market problems spill into a Japanese-like prolonged recession, causing a bear market? Every strategy should be evaluated not just on a "benefit of being right" basis, but at least as importantly on a "cost of being wrong" basis. An active value-investing strategy has the lowest cost of being wrong in comparison to other investment strategies, as you can see in Exhibit 11.

Exhibit 11

ߧ

Normxxx

______________

The contents of any third-party letters/reports above do not necessarily reflect the opinions or viewpoint of normxxx. They are provided for informational/educational purposes only.

The content of any message or post by normxxx anywhere on this site is not to be construed as constituting market or investment advice. Such is intended for educational purposes only. Individuals should always consult with their own advisors for specific investment advice.