Inflation During The Great Depression

Puncturing Deflation Myths, Part 2

False Lessons From Japan

By Daniel R. Amerman, CFA, Inflationintowealth.Com | 21 March 2009

Overview, Part 1

As the financial crisis continues to deepen, many people are deeply concerned that collapsing credit availability will lead to powerful monetary deflation, much like it did during the US Great Depression of the 1930s. As compelling as these arguments seem to be— are they backed up by the actual historical evidence? In this article we will:

1) Ask a crucial real world question about deflation theories;

2) Revisit the US Great Depression with a focus on 1933 rather than 1929;

3) Show that the central monetary lesson of the US Depression is not the unstoppable power of deflation, but rather, the historical proof of how a sufficiently determined government can smash monetary deflation and replace it with inflation— at will and almost instantly, even in the midst of a depression;

4) Examine two historical and logical fallacies that lead to the mistaken (albeit widespread) belief that the Depression proves the modern deflationary case, when it in fact proves the opposite; and

5) Briefly discuss the third logical fallacy that threatens many investors’ standards of living over the years to come, particularly those who are retired or investing for retirement.

A Simple But Vital Question

I received a letter from "GW", an economically astute and well read person who had attended one of my inflation solutions workshops. GW said that I had made the most compelling case for inflation he had ever heard, but that he remained troubled. There were a lot of deflationists out there, and there were some highly intelligent and credentialed people who were making some powerful theoretical arguments for deflation. GW asked: would I be willing to debate some of those arguments with him?

I replied that I would, but I would only debate theory if he could first answer a simple, real world question. "Name an example of a modern, major nation where the domestic purchasing power (as measured by CPI) of its purely symbolic & independent currency uncontrollably grew in value at a rapid rate over a sustained period, despite the best efforts of the nation to stop this rapid deflation?"

GW thought he had two answers— the usual two of the United States during the Great Depression, and modern Japan. Understanding why neither of those answers is correct is the subject of this and the following article. This article, Part 1, will be devoted to uncovering some lessons from the US Great Depression that will surprise many readers, while Part 2 will separate truth from fiction regarding Japan’s deflationary struggles, even as it separates asset deflation from price deflation.

Please carefully note the bolded and italicized words in the central question above. They are essential. Consumer price deflation has a long and sometimes infamous history, as we will discuss below. However, a specific argument being made by many observers is that the United States (and other major modern economic powers) run the risk of falling into a powerful deflationary trap as the availability of credit collapses, the volume and velocity of money shrinks, and this combination will then lead to major and rapid monetary and price deflation that the government will be powerless to stop. On paper— some powerful theoretical arguments appear to exist to support this assertion.

However, before millions of investors shift their portfolios to protect themselves from 'unstoppable' deflation, or neglect to protect themselves from inflation because they do not know whether the future holds inflation or deflation— isn’t it worthwhile to first demand that proof be provided of at least one fully relevant real world case study where this actually happened? Simply stated:

Where’s The Beef?

What is the specific example of a modern, major economic power proving powerless to stop the rapid rise in the domestic purchasing power of its own independent currency, as measured by the CPI?

And if such a deflationary example cannot be produced and defended— but we do have a very long and repeated history of inflation across nearly all modern nations with modern currencies— is this not the single most important data point that individuals should consider in weighing the relative risks of monetary deflation versus inflation?

The Great Depression: A Succinct Statistical Summary

The Dow Jones Industrial Average reached a peak of 381 on September 3, 1929. By July 8, 1932, it had reached its floor of 41, a plunge of 89% in less than 3 years. (This is a historical tidbit that those who think they are "bottom fishing" at current stock market levels should keep in mind.) The United States Gross Domestic Product was $103 billion in 1929. By 1933 it had fallen to $56 billion, a decline of 46%.

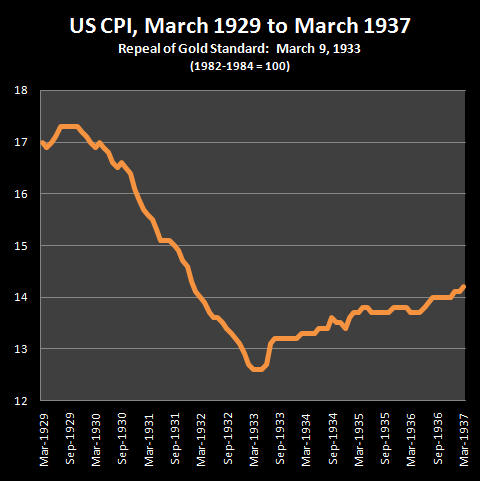

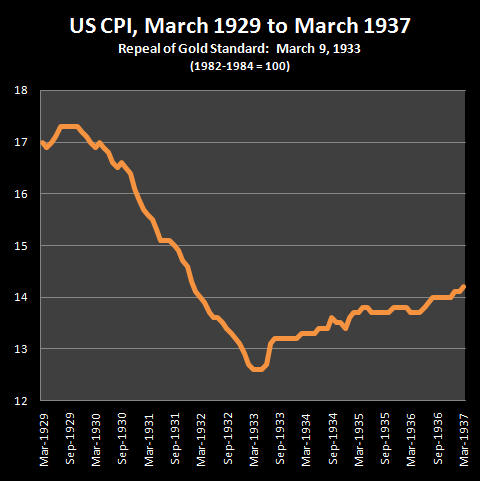

Accompanying the freefall in both the economy and the markets, price levels were falling as well— meaning that the value of a dollar was rising rapidly. The Consumer Price Index was at a level of 17.3 in September of 1929, and by March of 1933 had fallen to a level of 12.6. This means that what cost $1.00 in 1929, cost 73 cents (on average) by 1933. This 27% deflation, this fall in the average cost of goods and services, represents a 37% increase in the purchasing power of a dollar.

For some people, the effect of this deflation was to increase both their wealth and their standard of living. These are the people who had substantial money savings, either in physical cash, or fixed denomination financial assets that survived the economic turmoil, such as accounts in banks that did not go bust, or the bonds of companies that did not default. For these individuals, all else being equal, their standards of living rose because they had the same amount of dollars, and each dollar bought more than it had previously.

However, this increase in the value of a dollar was achieved at great cost for most of the nation (and the world). The reason for the increase in value was that dollars had become scarcer for businesses and most individuals. The destruction of the banks and much of the financial markets had dried up access to money on attractive terms. Widespread unemployment meant fewer dollars available to buy goods and services, which drove down the prices, which is what dropped the Consumer Price Index.

Most importantly, the deflation was not independent of the plunge in the markets and economy, and not just as a result, but most economists agree that this monetary deflation was actually a reason why the Great Depression got as bad as it did. Because there was not enough money, the source of funding for growing businesses was gone. Because there was not enough money, and the money outstanding had grown too dear, consumers were not spending.

Because there wasn’t enough spending, businesses had to lay people off. Which further reduced consumer spending. The nation was caught in a vicious deflationary cycle, which it seemingly could not break out of.

Yet, the United States did break out of the deflationary cycle, as illustrated in the graph above. After rapidly plunging for about 30 months, with the CPI seemingly in free fall and not able to find a floor— there was an abrupt turnaround. Not only was a floor found, but an immediate cycle of inflation replaced the seemingly unstoppable deflation. The nation turned essentially "on a dime", from unstoppable deflation to inflation instead. A cycle of inflation that has continued until this day.

What Happened? March 9, 1933

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933. He came into office with a mandate and agenda to stop the Depression, and that meant breaking the back of the deflationary spiral. His actions were swift, beginning with a mandatory four day bank holiday imposed the day after his inauguration.

Five days after Roosevelt took office, on March 9th, the Emergency Banking Relief Act was passed by Congress. This was the first in a series of executive orders and bills that would take place over the following weeks and year. These actions would cumulatively take the United States government off the gold standard— and would also effectively confiscate all investment gold from US citizens at a 41% mandatory discount.

From 1900 to 1933, the US government had been on a gold standard, and had issued gold certificates. In a matter of days, in March of 1933, there would be a radical change. A veritable 180 degree turn that would not only repeal the gold standard, but effectively make the use of gold as money illegal in the United States.

Fallacy One: Confusing Apples & Oranges

There is a common simplification that people make when they look at money over time. They think that a dollar is a dollar, even if the purchasing power has changed a bit. This is a quite understandable mistake, particularly if your profession does not involve the study of money. When we look back over history— nothing could be further from the truth.

This assumption instead reflects an elementary logical error, that may be quite dangerous for your personal future standard of living, if it leads to your drawing the wrong conclusions. The term "dollar" is only a name (the same holds true for the "pound", "franc", "peso", "mark", and all other currencies). What matters is not the name, but the set of rules— or collateral— that back the value of the currency, during a particular historical period.

When we look back over long-term history, then sometimes it is gold, sometimes it is silver, sometimes it is both, and sometimes it is something else altogether. (As a creature of politics, "money" has always been of a complex and quite variable nature, given enough time.) So when we say history "proves" something about a currency, we need to be very, very careful that we are talking apples and apples, rather than apples and oranges.

For instance, when we look at precious metals backed currencies, the deflation of 1929 to 1933 when the US was on the gold standard was nothing new. It was just the latest development in the ongoing cycle of inflation and deflation that characterizes this type of currency. Indeed, there were four major deflations during the century before Roosevelt ended the domestic gold standard, and the deflations of 1839-1843 and 1869-1896 were each much larger than the deflation of 1929-1933, with the dollar deflating roughly 40% in each of those earlier major deflations.

This deflationary history does not, however, reflect the value of the "dollar" (as we currently know it) bouncing up and down, but rather the value of the tangible assets securing the dollar bouncing up and down around a long term average. Going off the gold standard was nothing new either. Many nations have gone through periods, particularly during wars, when more money is needed than there is gold or silver to back it up.

So, they issued 'symbolic' (fiat) currencies that were backed only by the authority of the government, or debased the metals content of the coins. These fiat currencies almost always turned out badly. Instead of cycling up and down in value over time, they tended to go straight down and never come back up. [[But herein also lies a story, because when the value of the Weimar Mark essentially fell to zero, what replaced it? Why, just another type of Mark, an ArbeitsMark, also without any gold or silver backing, backed only by the "labor" of the German people. Nevertheless, it was accepted at par and did not suffer the fate of the Weimar Mark until the end of the Third Reich.: normxxx]]

While global monetary history is complex and long, it is highly, highly unusual for a symbolic currency to experience major and sustained deflation at the levels that are the norm with precious metals backed currencies. It is this quite understandable but wrong belief that a "dollar" is a "dollar" that creates the ironic situation of many millions of people believing that the deflation of the US Great Depression proves the case for deflationary dangers in the current crisis. Not at all— what we have instead is the elemental logical fallacy of mixing up apples and oranges.

Yes, the US experienced powerful monetary and price deflation during the early years of the Great Depression, but that was with a dollar that was backed by gold. A currency in other words, that has almost nothing to do with today’s dollar, other than the name. A currency type whose long term history is radically different than fiat currencies— such as the dollar today.

Fallacy Two: Reversing The Historical Lesson

Let’s revisit the sequence of events and what actually happened. The United States was stuck in a powerful deflationary spiral with a gold-backed currency, that seemed unstoppable. A currency that had little to do with what we call the dollar today, other than sharing the name.

So, the government changed the rules, and replaced the old dollar with a new dollar, whose value was not based on gold. A dollar much like we have today (albeit not quite the same as there was still a gold backing on an international basis). And what happened?

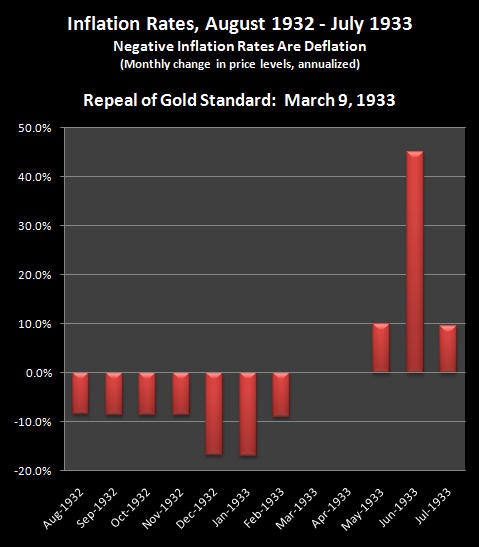

In the depths of depression, at the height of a deflationary spiral, the government successfully broke the back of deflation within one week. In the midst of deflationary pressures far greater than we are seeing today, the government not only stopped the deflation, but replaced it with inflation. Indeed, by May of 1933, only two months after the currency rules changed, the monthly rate of inflation hit an annualized rate of 10%, and even hit a 40%+ plus (annualized) monthly rate by June of 1933. [[FDR's original "brain trust" foolishly thought that if they broke the back of monetary deflation, the depression would end. It was not to be.: normxxx]]

If you’re concerned about a new US depression leading to unstoppable price or monetary deflation because of what happened in the 1930s, let me suggest that you study and remember the graph above. When you get worried about monetary deflation— take another look at March of 1933. Remember as well, the one near universal lesson from the long and convoluted history of money: every time the rules governing a currency lead to a problem that causes too much pain for a government to bear— the government just changes the rules.

The bigger the problem— the bigger the rules change [[hence, TEOTWAWKI*: normxxx]] (and the bigger the wealth redistribution). So, when we look not at near irrelevant gold certificates, but at the dollar we have today, what the Great Depression of the 20th century in the United States historically proves is not the unstoppable power of deflation, but the opposite: that a sufficiently determined government can smash monetary deflation at will, virtually instantly, even in the midst of depression, and replace it with monetary inflation.

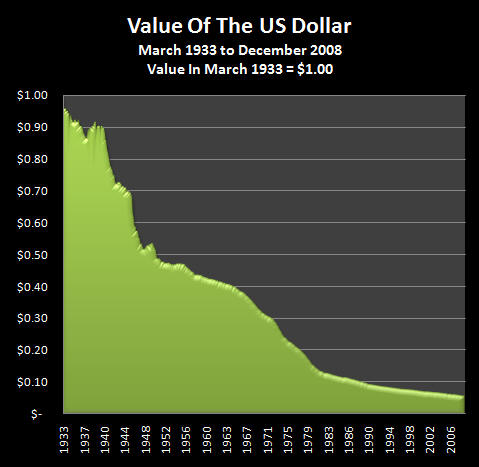

In the process of breaking the back of deflation (in 1933)— the nature of the dollar itself fundamentally changed. Throughout the 19th century and the first 30 years of the 20th century, the value of the dollar fluctuated up and down, as the (usually) gold-backed currency experienced regular cycles of both inflation and deflation. This cycle was replaced entirely by a new pattern— which could be characterized as down, down, down, as illustrated in the graph below.

(The graph above may look like it starts at 95 cents, but it doesn’t, it starts at $1.00. The fall in the value of the dollar in 1933 once the gold standard was abandoned was so fast it can’t be seen with a 75 year scale and monthly increments.)

A 76 year old person born in the 19th or 18th centuries would have seen the value of his or her currency fluctuate up and down over their lifetimes, and there was a pretty good chance that at age 76, the dollar (or pound) would have been worth the same or even more than it was when they were born. When the US Government fundamentally changed the nature of "money" in 1933, it created an entirely different pattern— all down, and no up, so that for a 76 year old person today, a dollar will only buy what 6 cents did at the time they were born.

As we try to decide whether the danger ahead is inflation or deflation today, what is the monetary lesson for us from the US Great Depression? The common belief is to say the Great Depression proves the awesome power of deflation, that the government can have a great deal of difficulty in fighting it, and may not be able to fight it at all. This is an extraordinary misunderstanding, and constitutes the second of our logical and historical fallacies.

What the Great Depression showed was that if you have a tangible asset backed currency, such as by gold or silver, and you enter a depression, then history has shown time and again that you're likely to have a period of substantial monetary deflation. However what March of 1933 showed us, is that even in the midst of a terrific burst of asset deflation, even in the midst of a terrible depression, if you take away the tangible assets that back your currency and you introduce a purely 'symbolic' currency, then the force of inflation that is associated with a purely symbolic currency (as well as the changes in monetary policy that are thereby enabled) can be so powerful that it overcomes the depressionary economic pressures and forces monetary inflation. [[The value of money has little to do with its 'backing' and much to do with its scarcity. Money backed by gold or silver is limited in quantity, and so its value cannot decrease greatly, as that would mean either that the value of the backing was diminishing or that the amount of backing per dollar had been reduced. In effect, the backing acts as a sort of discipline which prevents the wholesale, uncontrolled 'production' of dollars.: normxxx]]

Indeed what March of 1933 showed is that the value of money can turn on a dime when we are using a symbolic currency [[whose value can be regulated simply by increasing or decreasing the amount of dollars in circulation.: normxxx]]. We thus have absolute proof that even in the middle of a depression, the government has the power to stop a deflationary spiral at will. We know, further, that this deflation fighting strategy was not a one time anomaly, but was so successful that it broke the historical cycle of inflation/ deflation , and led to a 94% destruction of the value of the dollar over the next 76 years. [[But, on the other hand, the benefit has been that we have escaped severe depressions and asset deflations and only retirees have suffered, since wages and assets have more or less kept even with the money inflation, until now.: normxxx]]

It is a great irony that this lesson is so widely misunderstood. Unfortunately, this misunderstanding is highly dangerous for investors, as it leads them to worry about what is likely not a problem, instead of concentrating on the grave dangers illustrated by this same historical example. Dangers that involve the simultaneous combination of asset deflation (the destruction of the purchasing power of your assets) and monetary or price inflation (the destruction of the purchasing power of your money). As I have written about in other articles and books, these are a potent wealth destroying combination with a long history of destroying wealth in general— and retiree wealth in particular— in societies that are in economic distress.

Some People Understand What Happened Very Well Indeed

While misunderstanding what happened in the Great Depression is common, it is not at all universal, particularly among economists. Indeed, what really happened during that period between 1929 and 1933 has been a career-long source of fascination for one important economist in particular: Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Federal Reserve. Bernanke believes that a major mistake was made— and it wasn’t abandoning the gold standard.

No, Bernanke’s quite public belief is that the economic contraction that was the Depression was much deeper and longer than it needed to be, and the reason was that monetary stimulus was too small and too late in coming. In other words, his belief is that if the rules governing the nature of the US dollar had only been changed earlier, so that there was inflation instead of deflation by 1930 or 1931, the economic devastation inflicted on the nation by the deflationary spiral would have been much less. (Some economists look to the example of Japan abandoning the gold standard in 1931, two years earlier than the US, and the shallower and shorter economic contraction that was experienced there.)

Bernanke got his nickname of "Helicopter Ben" from a flippant comment he made, in which he dismissed deflationary fears with a joke about dropping money from a helicopter if needed. This is a very important joke, with drastic implications for your personal net worth. Instead of fearing deflation, Bernanke finds fears about deflation to be humorous because he understands the principles described in this article very, very well indeed, and has for many years.

There are no immutable and awesome powers of monetary deflation that render governments helpless. Because once it is freed of its connections to precious metals or other currencies— money is really just a symbol with an inherent value of zero. [[But so is gold; what good is gold in the middle of a desert, you can't eat, drink, or shelter with it! But gold is scarce (and ornamental); hence its value. And, as Paul Volcker proved, when paper money is made scarce, it too will appreciate in value or, at least, nip inflationary tendencies in the bud.: normxxx]] What gives a national currency value are the rules that are set up by the government. And if the rules become inconvenient, well, what’s the point in being in power, if you can’t change the rules when you need to?

Changing the rules is not a theory about what Bernanke might do. It is a description of what he has already been doing on a massive scale. The self-imposed shackles that used to restrain past Fed chairmen are already history. The Fed is creating money at a rate never seen before, trillions of dollars a month, effectively out of thin air.

The Fed typically doesn’t do this, because, of course, such actions rapidly destroy the value of the currency. But if the person in charge of the money supply understands that destroying the value of the currency is how you prevent deflationary spirals from getting started— and believes massive and fast government intervention is the best way to stop an incipient depression before it gets any worse— then much of what the Fed has been doing recently becomes much more understandable.

The Third & Most Dangerous Fallacy

Our first fallacy was the widespread belief that the Deflation of 1929 to 1933 proved that major deflation is a major risk for a nation in depression. What it actually proved was that deflationary spirals are a major risk for gold-backed currencies, even while providing concrete historical evidence that symbolic currencies which are backed by nothing but government policies (such as the dollar today) can be forced into inflation even in the very middle of a severe depression.

Our second fallacy was believing that price deflation can grow so powerful that it can render a country’s monetary policy almost helpless to fight it. But what March of 1933 showed is that a sufficiently determined government can break the back of monetary deflation at will and almost instantly, simply through changing the rules that govern the value of that currency. (The far more dangerous problem of asset deflation is a quite different matter, as we will explore in Part 2.)

There is a third fallacy which is perhaps the most important, and that is the belief that inflation or deflation changes wealth for the nation as a whole and there's nothing that you personally can do much about it. This belief that we are all in the some boat together is perhaps the most dangerous mistake of all for individuals seeking to protect their wealth. Inflation and deflation do have an impact on the real wealth of society, they do affect the creation of real goods and services, and impact the real GDP, but they also do something else that is every bit as powerful, that is even more immediate and that is deeply personal. What inflation and deflation do is that they redistribute the rights to wealth within our society.

When we look back to the Great Depression in the years 1929 to 1933 then, for retirees at that time who did not have their savings in the market or in banks that went bust, those were actually good years for them financially, particularly relative to the rest of the population. Monetary deflation redistributes wealth from society at large to many retirees. However, sustained, major monetary deflation with a symbolic currency is quite rare, and hasn’t happened in modern times.

This brings us back to that central question regarding the case for deflation: "where’s the beef?" Where is that example of "a modern, major nation where the domestic purchasing power (as measured by CPI) of its purely symbolic & independent currency uncontrollably grew in value at a rapid rate over a sustained period, despite the best efforts of the nation to stop this rapid deflation?" If actual history is what matters to you rather than theoretical discussions, unfortunately, we have a long history of what happens with nations in severe economic distress, when they have a symbolic, independent currency (not explicitly tied to another currency) [[ie, one whose production is not in any way constrained: normxxx]].

That history is that NOT one of those fiat currencies soared in purchasing power, despite the best efforts of the economically wounded nation to keep that from happening. No, the very well established pattern is that the currency collapses in value (price inflation) as the central authorities increase its production to 'stimulate' the economy, even as the purchasing power of assets is collapsing (asset deflation), much like what is happening with Iceland today. That collapse in the value of the currency necessarily forces a major redistribution of wealth, and the segment of the population that is most devastated by this seems always to be the same. It’s the retirees, and the people close to retirement. When we look to Germany, when we look to Argentina, when we look to Russia— it is the pensioners who are impoverished more than any other group [[as in the U.S. in the '70s: normxxx]].

Unfortunately, history is repeating itself once again. When we look at the headlines about the destruction of retiree investment values, pension assets and so forth, we're really just seeing the beginning. Because the crisis "solution" that is being chosen, which is to creating dollars without restraint, essentially represents the annihilation of most of the retirement dreams of the baby boom generation, even if that is not yet recognized.

There is not an even cost that is being born by society as a whole, rather some segments are bearing much more of the burden than others. If your peer group (particularly Boomers and older) is headed for disproportionate financial devastation, then happenstance is unlikely to offer a personal way out. Instead, you must take quite deliberate actions to change your personal financial position so that wealth is redistributed towards you, rather than away from you.

.

False Lessons From Japan

Puncturing Deflation Myths, Part 2

Overview

In Part 1 of this series on Puncturing Deflation Myths, we reviewed three logical fallacies, and showed why the US Great Depression didn’t prove the case for monetary deflation, but rather provided historical proof of how a sufficiently determined government could break monetary deflation at will, even in the midst of depression. In this Part II we will uncover three more logical fallacies as we:

1) Revisit our central question with regard to widespread theories about rapid and uncontrollable price deflation threatening symbolic currencies ("when has it ever happened in the real world?") and review what actually happened with modern Japan;

2) Show the true peril experienced by Japan over the last 20 years, which is not monetary deflation but the much more deadly asset deflation;

3) Uncover the extraordinarily dangerous logical fallacy that results from confusing the two types of deflation, and show how this fallacy is currently leading millions of investors to mistakenly believe the value of their money is protected by bad economic times— when it has no protection at all;

4) Briefly discuss why individual investors need to leave conventional financial wisdom behind and explore "outside of the box" solutions to these pressing issues.

Japan & "Where’s The Beef"?

As discussed in Part One, I asked whether one of my questioners could

|

The two common answers to this question are the United States during the 1930s (which was addressed in Part I) and modern Japan. But does Japan meet the conditions of this central question? Does it provide the real world "beef" for justifying theoretical monetary deflation fears?

Clearly Japan and the yen meet the criteria for modern, major, and symbolic. How about the domestic purchasing power of its currency uncontrollably growing at a rapid rate over a sustained period, despite the best efforts of the nation to stop this rapid deflation? After all, that is the very heart of the deflationist case for the US: that collapsing availability of credit will shrink both the volume and velocity of money, creating a rapid, powerful deflation that the government will be powerless to fight. Is that what happened [[or is still happening: normxxx]] in Japan? (Or anywhere else, ever, with a symbolic currency?)

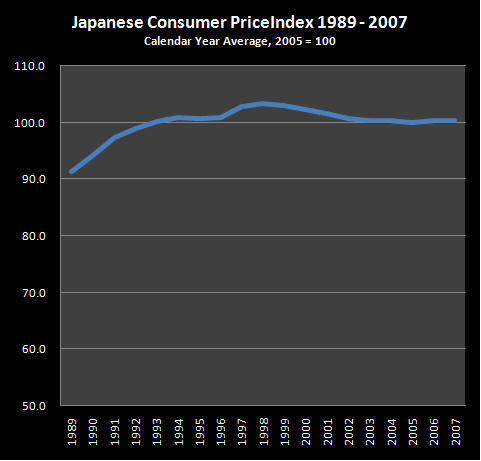

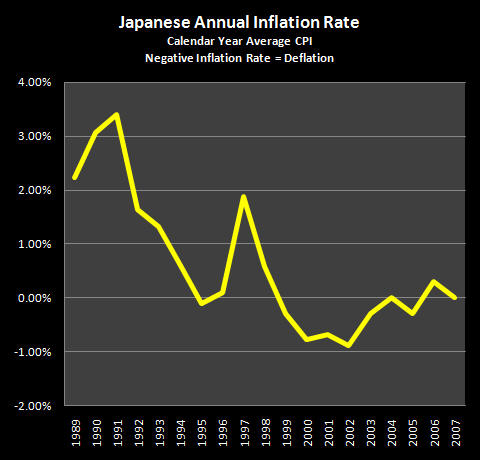

Maybe the best place to start is to see what actually happened to the domestic purchasing power of the yen during its time of economic "troubles". The graph below tracks the average annual Japanese Consumer Price Index for the 19 year period from 1989 through 2007.

At first glance, that’s a pretty boring graph. Where is the drama and the action? Like that of the graph below from Part One of this article, which shows the US CPI during the Great Depression of the 1930s:

After looking at the US Consumer Price Index from 1929 to 1933 (or most global currencies during that period), the example of modern Japan looks quite tame in comparison. Where is the massive plunge? Where is that out of control monetary deflation that Japan was powerless to stop?

By historical standards, modern Japan clearly has not experienced major price deflation, not at all like the levels experienced by the US in the 1930s (and many nations at that time), or the bouts of severe deflation that hit repeatedly in the 1800s, when these nations were on a gold standard (as covered in Part I). Maybe this symbolic currency monetary deflation is there but is hard to see? If it’s hard to see on a big graph with cumulative CPI, maybe we need to narrow our focus and look at annual changes in the value of money:

When we look at the actual history of price (CPI) deflation in modern Japan, we can easily see:

1) At its worst— Japanese price deflation never reached even 1% per year, comparing average annual CPIs.

2) During the 19 years following the crash of the Nikkei, there where only 6 years of minimal deflation, and 13 years of inflation.

3) On a cumulative basis over these 19 years, Japan experienced price inflation, not price deflation. Indeed, the domestic purchasing power of the yen fell by 9% between 1989 and 2007, as shown in the first graph, "Japanese Consumer Price Index, 1989-2007".

@@

The Fourth Fallacy

When we put these three historical facts together, then we have our fourth common deflation fallacy (the first three fallacies are in Part One). This fallacy is the widespread belief that Japan experienced a powerful price deflation that it was unable to combat. In fact— the rate of price deflation never even reached one percent per year. This was an almost infinitesimal amount, and even a slight change in the calculation methodology could have shown no deflation at all!

Also of importance is that arguably much or even all of Japan’s minor price "deflation" resulted from increasing imports of cheaper goods from other nations, which has nothing to do with the 'collapsing credit' of deflationist theories. Falling rents are the other main factor, but remove those imported goods, and the minor deflation disappears. The New York Times article from 2001, "Japanese Consumers Revel In Deflation's Silver Lining", is an easy-to-read treatment of what real world modern monetary deflation was like at the peak of Japan’s recent experience. That may be an eye-opener for many readers.

This import driven (minor) price deflation, which was also key in slowing inflation in the US in the same time period (simply think China and Wal-Mart rather than esoteric macroeconomic theory), is a very different "animal" from 'collapsing credit availability'— and therefore irrelevant to proving the argument. What also needs to be clearly understood is that this deflation is not independent of government policy, but is the direct result of government policy— the easing of import restrictions to increase the size of the overall economy. Japan could have almost instantly stopped its price deflation at will by simply changing import regulations.

Now granted, Japan has entered into international agreements to allow freer access to its domestic markets, as has the US, and there is the possibility that falling import prices from lower cost nations desperately trying to escape their own depressions could exert significant deflationary pressures in the future. But only if the governments let that happen. These free trade agreements came about because the developed nation’s citizens were assured economic prosperity in exchange for effectively allowing the destruction of many of their domestic industries.

Replace promised prosperity with actual depression, let the political cycle go around a time or two, and import driven deflation is something that can and possibly will be stopped immediately in many or most nations. Because import driven deflation is not an unstoppable and independent economic force, but a creation of the political process. When we return to our question asking for the single real world example of a symbolic currency rapidly and uncontrollably gaining in domestic purchasing power, despite the government’s best efforts to fight it— Japan clearly does not qualify.

So, once again— where is that real world example? Do make sure you get an answer before betting your net worth on a theoretical argument about the inevitability of powerful and uncontrollable price deflation caused by a collapsing credit bubble, which governments will be powerless to fight.

Japan’s Catastrophic Experience With Asset Deflation

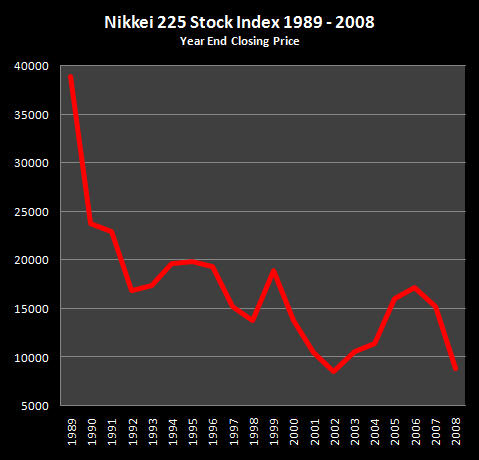

However, this is not to say that Japan hasn’t experienced powerful deflation over the last 20 years. Japan has indeed experienced major, even catastrophic deflation, that has savaged investor wealth and reduced the standards of living of many millions of Japanese as result— particularly retirees. If you want to see a spectacular (and dismal) graph of Japanese deflation, here it is:

At the peak of the Japanese asset inflation bubble of the late 1980s, both the stock market and real estate market were hitting extraordinary highs, where the ability of companies to earn profits, and the ability of homeowners to make mortgage payments, had become almost irrelevant to stock and real estate prices. What mattered was price appreciation, and the more insane prices grew, the more investors piled in, to enjoy the fantastic paper profits that could be earned on the ride up. That is, until the cycle turned, and the bubbles popped.

The Nikkei hit 38,916 by the end of 1989 at the height of the exuberance— and then cold, hard reality started to hit. The Nikkei fell to 23,848 in the next year (down 39%), then 22,983 (down 41%), and then 16,924 by the end of 1992 (down 57% in 3 years). The full fall took 13 years, with the Nikkei 225 reaching 8,578 by the end of 2002, a 78% fall— something investors in other nations who are tempted to go bargain hunting today should keep in mind. This is deflation of the very worst kind for investors in general and retirement investors in particular— but it is NOT price or monetary deflation. It is something far more dangerous, and that is asset deflation.

Price deflation is about falling prices for the goods and services you need to live and enjoy life. Because the prices for the things you need to buy are falling— your money buys more, meaning your real wealth is rising, all else being equal. Asset deflation is about falling prices for the substantive assets that you have— such as your house and your investment portfolio. Because the prices for which you can sell your assets are falling, your assets buy less, meaning your real wealth is falling.

Both deflations are about falling prices— but that is where the similarity ends. The two deflations have opposite direct effects on your standard of living. The direct effect of price deflation is to raise your standard of living, and the direct effect of asset deflation (assuming you are selling rather than buying) is to lower your standard of living. So, really, we are talking about two quite different kinds of deflation, which may have opposite effects on the standard of living of many people.

The Fifth Fallacy

Unfortunately, many financial commentators don’t understand the difference between the two fundamentally different kinds of deflation. This leads to our fifth logical fallacy in this series, and a return to the basic problem of comparing apples to oranges. In Part I, the apples and oranges fallacy was taking a history of price deflation based on gold-backed currencies, and saying it applies to purely symbolic currencies— despite the radically different long term histories of the two different types of currencies. Our fallacy in Part II is mixing up two quite different types of deflation.

This lack of differentiation leads to the mistaken belief that Japan proves the case for modern price or monetary deflation. It doesn’t do anything of the sort— what Japan proves is the case for asset deflation— which is a quite different thing. This confusion of terms is a deadly danger for individuals— and it really isn’t their fault.

Economics professionals are of course well aware of the difference between the two types of deflation. When you look at academic texts such as "Deflation: Current and Historical Perspectives" by Burdekin and Siklos (Cambridge Press), it is about modern asset deflation, price deflation in the 1930s and before for gold-backed currencies, and theories about whether monetary deflation will return as a major danger. This same model, which quite explicitly distinguishes between historical price deflation from the 1930s, actual modern asset deflation, and theoretical modern price deflation dangers, also applies to such works as the findings of the International Monetary Fund’s deflation task force, as reported in "Deflation: Determinants, Risks and Policy Options" (2003) by Manmohan S. Kumar et al.

However, few people read such works in the original. Instead, the information must pass through a filter, with the largest filter being the mainstream media. If the members of the media don’t understand the difference— their readers and viewers certainly won’t either.

Indeed, in a world where it is exceedingly rare for the mainstream media to do something so basic and essential as report stock indexes and gold prices in inflation-adjusted terms, it should come as no surprise that the distinction between price deflation and asset deflation only rarely appears. Which leads most people, even very well read and highly intelligent people, to believe that there is essentially only one kind of deflation— a mistake that can have devastating consequences for individuals and the value of their savings, as we will review in our sixth fallacy. This differentiation between asset deflation and price deflation is very well understood by one particular group of professionals— and those are Japanese economists.

Kazuo Ueda, Member of the Policy Board for the Bank of Japan, wrote an article specifically to address the popular confusion about what was happening in Japan, and the difference between general price and asset deflation. Here are two key quotes:

|

The implications of this long fall in asset prices are extraordinary for investors in the United States and other nations. Indeed one could argue that the financial planning and pension management industry in the US was based upon a mutual agreement by everyone involved to close their eyes and pretend that Japan didn’t exist, with the full complicity of the government and academic community. To discuss what happened in Japan, and its vital implications for the US and other nations at this time, requires another full article, which will be part 3 of this series.

The Sixth Fallacy

Our sixth and most dangerous fallacy is the widespread belief that deflation protects us from inflation. This belief is false and indeed constitutes a deadly danger, because so many millions of people erroneously believe that falling asset prices protects the spending power of their money. On the face of it— deflation protecting us from inflation looks so obvious, that it would seem it would have to be true.

If inflation and deflation are opposite and opposing forces— how could you possibly have both at the same time? Common sense therefore tells many people that as they read headlines about falling prices, one side benefit is that at least for now, they can stop worrying about inflation. Unfortunately, this is a false sense of security that is based on the mistaken belief that there is only one kind of deflation, and that there is ample historical proof for this type of deflation.

The common belief is that depressions generate monetary deflation, so inflationary dangers at least temporarily go away. Quite simply, this has never happened with a modern symbolic currency, not in a way that meets the requirements of the question posed earlier in this article. Collapsing credit availability and the resulting collapsing money supply leading to an unstoppable and rapidly rising value for a symbolic currency (price deflation) is a popular theory— but it has never happened in the real world.

(At its core the theory is based on the naïve belief that a symbolic currency has some kind of inherent value aside from the rules which the government sets up, or that governments won’t change those rules when they have a strong incentive to do so. As discussed in my article "Why Inflation Will Trump Deflation", the power of a government to reduce or destroy the value of its own symbolic currency is absolute.)

There is an extraordinary and well proven danger from catastrophic deflation when leaving bubbles behind and entering a depression or severe recession, but this deflationary danger isn’t monetary deflation— it is asset deflation. The core of the danger is that asset deflation does NOT provide protection against monetary inflation. Instead, asset deflation and price inflation have a long history of occurring simultaneously in economically troubled nations, and working together to destroy wealth.

Meaning that an investor who does not understand the difference between the two types of deflation, and therefore doesn’t maintain strong defenses against monetary inflation— is effectively "bare naked" as a result. For, just because the value of your assets is plunging, does not mean the value of your money is safe, not at all. Basing their financial strategies on this false assurance, many people are failing to take protective measures against inflation, even as they clearly see the Federal Reserve creating money without limit in tandem with the US government creating bailouts without limit. [[And the Europeans, who have a long history of uncontrolled monetary inflations, have largely refused to "go along.": normxxx]]

When we look at collapsing credit and deflation— the relationship is very real and historically proven. Bidding up the prices of assets, or asset inflation, is often the result of cheap and easy credit financing the purchases of the assets. When the credit cycle tightens, then the lack of financing helps drive asset prices down, and a severe credit tightening like the current one can drastically drive prices down for a very long time. But, that the combination of collapsing credit availability and the resulting collapsing asset prices will lead to old-fashioned (gold standard type) major and unstoppable general price deflation— well, that is pure speculation. It's never happened!

The Difference Between Theory & History

Let's re-examine the example of Japan. If we look at the value of the stock market, when everyone had purchased stocks in expectation of unending wealth, and that stock market is now down 80% on an after-inflation basis— where is the protection? Even in the face of an 80% asset deflation in real terms over a 20 year period, the Japanese yen is still worth less than when the period of deflation started. The massive asset deflation obviously did not protect the value of the currency.

It is also important to keep in mind that Japan is a poor example of economic "troubles"— it is a nation of a mere 127 million people, lacking most natural resources, which managed to maintain its position as the world’s second largest economic power for two decades of "troubles" (before accounting for Chinese currency manipulation, anyway). It is this continuing strong economic performance (compared to the rest of the world) that accounts for Japan’s currency losing so little of its value. For another real world example of how the value of the currency can fall simultaneously with the value of assets, let’s look at the world’s number one economic power: the United States.

The US hit a period of economic turmoil between 1972 and 1982. The Dow stood at 929 in June of 1972, and by June of 1982 it had dropped to a nominal 812. It lost 13% of its value, and on the face of it, this is an example of moderate asset deflation. However, something else happened between 1972 and 1982: the dollar lost 57% of its value. When we adjust for inflation, the Dow Jones Industrial Average actually dropped from 929 to about 350 (in 1972 dollars), meaning it lost 62% of its value (exclusive of dividends).

That 62% reduction in value is powerful asset deflation— but here’s what that deflation and economic turmoil didn’t do— it didn’t protect the value of the dollar. A 62% drop in the purchasing power of assets did not protect the dollar from a 57% decline in its own domestic purchasing power. The ability of powerful asset deflation to protect the value of the currency failed spectacularly in practice.

Remember— the above is reality. A reality that has happened again and again in nations around the word that have gone through much worse economic stress than that experienced by the United States. Look at Iceland today. Or such well known examples as Argentina or Germany (or Zimbabwe) during their own bouts with high levels of inflation.

In each case the purchasing power of assets was plunging simultaneously with the purchasing power of the currency. Which is exactly what you would expect for a nation in depression. The idea that going into a depression necessarily increases the value of that nation’s symbolic currency, when the currency is essentially backed by the economy, is a bit unusual when you think it through, and therefore the lack of historical precedents is not surprising.

The Six Fallacies

Let’s quickly review the six fallacies we have covered in Parts 1 & 2 of this article.

Fallacy One. The belief that a "dollar" is a "dollar" and that the deflationary history of gold standard currencies applies to symbolic currencies (an "apples to oranges" fallacy).

Fallacy Two. The belief that the US Great Depression proves the case for unstoppable monetary deflation during depressions, when it in fact proves that a sufficiently determined government can immediately break monetary deflation at will, even in the midst of depression.

Fallacy Three. The belief that inflation and deflation take wealth from all of us equally, when what they actually do is redistribute the wealth among us.

Fallacy Four. The widespread belief that Japan experienced powerful price deflation that the government was powerless to fight. It didn’t.

Fallacy Five. The fundamental mistake of thinking that "deflation" is "deflation", which leads to confusing 'price' deflation with 'asset' deflation, and means missing the real lessons and dangers of what happened in Japan, which is the persistent asset deflation that has defeated all government interventions (another "apples to oranges" fallacy).

Fallacy Six. The dangerous belief that deflation protects you from inflation. More specifically, the vocabulary confusion that leads to the belief that asset deflation protects you from monetary inflation, or that the destruction of the value of your assets is somehow historically proven to protect the value of your money.

The six fallacies reviewed in this and the previous article come as quite a surprise to many people. We uncovered those fallacies— by improving our vision. Interesting though this is, a better understanding of what has happened in the past is not the primary reason for improving our inflation and deflation vision.

More importantly, improving our vision allows us take personal actions for the future. As your vision improves further, you will come to understand that what all forms of inflation and deflation share is that they are redistributions of wealth among the individuals within a society. When we raise the degree of inflation and/or deflation, then we increase the opportunity for you have to have wealth redistributed to you by these fundamental economic forces.

In contrast to the six fallacies— let’s consider what clear vision can look like:

The above slide (from one of my courses) is an illustration of simultaneous monetary inflation and asset deflation. The one-two combination that annihilates retiree wealth and the value of long term savings for other investors. Now if you believe that it is simply a matter of inflation versus deflation, and if you believe that all we're talking about is the destruction of wealth, then it is all too likely that your financial status in a situation like the above has been predetermined.

You will be a victim of inflation and a victim of deflation, both. These forces acting in concert will steal wealth away from you, and it may seem almost impossible to stop them if you are in the common situation of investing towards retirement and you have both substantial investment and monetary assets to protect. Because the double forces of monetary inflation and asset deflation will be working to simultaneously decrease the purchasing power for both your money and your investment assets.

There is hope, however. Indeed there are ways to take the situation introduced in the slide, where the value of your money drops by 75% and the value of your asset drops by 50%— and turn that into substantial profits on a tax-advantaged basis. Possibly some of the best returns of your life on an after-inflation and after-tax basis.

To get out of step with your generation, and have wealth redistributed to you even as your peer group is being devastated by this extraordinary destruction of wealth, you need to start with an essential and irreplaceable step: education. You need to gain the knowledge you will need to turn adversity into opportunity. This will mean looking inflation straight in the eye and saying:

|

Remember— redistributions of wealth mean some people do worse— and other people do better. The higher the degree of inflation and/or the degree of deflation— the greater the redistribution of wealth. We are coming into a period of one of the greatest redistributions of wealth in our lifetimes, with extraordinary pressures building for both monetary inflation and continuing asset deflation (remember Japan’s fall in asset values lasted for 13 years).

You have a choice to have wealth taken from you— or to find ways for wealth to be redistributed to you. To make proper use of that choice, you have to understand it fully, and all the nuances. Which means education. Otherwise, we’re just shooting in the dark.

TEOTWAWKI* The End Of The World As We Know It, ie, when some, many, or all of the 'accepted' rules of investment, politics, and living are liable to be (and likely to be) radically changed in an instant.

ߧ

Normxxx

______________

The contents of any third-party letters/reports above do not necessarily reflect the opinions or viewpoint of normxxx. They are provided for informational/educational purposes only.

The content of any message or post by normxxx anywhere on this site is not to be construed as constituting market or investment advice. Such is intended for educational purposes only. Individuals should always consult with their own advisors for specific investment advice.

No comments:

Post a Comment